This article was originally published on Real Assets (January/February 2023 edition)

Could venture capital revolutionise farming and unlock cheaper food for the world? Florence Chong reports

The war in Ukraine has unleashed a multitude of flow-on impacts to a world still working its way through COVID-induced disruptions to the global food supply chain. Energy shortages are striking at the heart of agriculture, putting in peril the core sources of food production – ranging from fertilisers made in Russia to the power needs of new greenhouse technology.

Meanwhile, natural calamities – drought, famine, flood – provide constant reminders of the fragility of the world’s agricultural system. Farmers face a dilemma in seeking to stem steadily worsening issues arising from over-cropping and soil degradation. These in turn have their roots in loss of biodiversity, desalination and desertification.

Some crops currently cultivated in certain parts of the world may start to fail because of changes to soil and climate. All this is taking place against a background of unstoppable growth in global population, which topped eight billion in November.

Yet, curiously, the wave of digitalisation which has brought positive disruption to many stratums of the international economy has largely had a limited impact on agriculture.

Where new technologies have been embraced at scale, as in the Netherlands, they have transformed agricultural production. The Dutch today are prolific producers of food, feeding western Europe and beyond.

The pace of technological change is slower in agriculture, partly because traditional farming practices are harder to change. Farmers need to invest and, at the other end of the spectrum, consumers are simply not prepared to pay more for sustainable food production.

“Since World War II, we have relied on fertilisers and genetics to give us the productivity to feed a planet of 6bn people,” says Sanjeev Krishnan, CIO of Chicago-based S2G Ventures. “Now we have to feed 8bn people – and that is rising to 10bn. Increasingly, we need to use natural resources responsibly. The silver bullet is productivity, and that is all about innovation. Innovation is all about start-ups.”

S2G Ventures, ranked by the industry as one of the world’s most active venture-capital (VC) firms in food and agriculture, manages around US$1bn across 65 companies in its food-tech and agri-tech funds.

According to Adam Anders, managing partner of Amsterdam-based Anterra Capital, food and agriculture is the remaining 12% segment of global GDP to go through a tech transformation. And those in the industry believe the current global tech wreck destroying the valuations of many leading global companies could throw up investment opportunities for investors in the agri-tech sector.

Bor Boer, principal at Convent Capital’s AgriFood Growth Fund, has “dry powder” from his firm’s first agri-tech fund launched earlier in 2022. He says there will be opportunities to step up investment in coming months.

Some investors are actually encouraged that the slump in tech investment has yet to spread to agri-tech and food-tech. Malcolm Nutt, partner at Australia-based Cultiv8 Funds Management, says that, despite a pullback in e-commerce and novel food products, funding is still available for these sectors. “We believe this is a long-term trend. We are comfortable that the agri-tech sector has a lot of tailwinds that will get it through these volatile times.”

The first Cultiv8 Agriculture and Food Technology fund was recently launched, targeting A$100m. “We should have three or four investments by the end of the year,” says Nutt. “We co-invest in some global projects.”

Cultiv8 invests in seed-to-series-B funding rounds, with Nutt expecting the investments to be split between Australia and overseas. His firm has previously invested in projects such as FutureFeed, which is turning asparagopsis (seaweed) into cattle feed to reduce methane production from the herd.

“FutureFeed has issued seven licences,” he says. “These companies have raised approximately A$70m to manufacture the product and hopefully roll it out to Australian feedlots and dairies in 2023.”

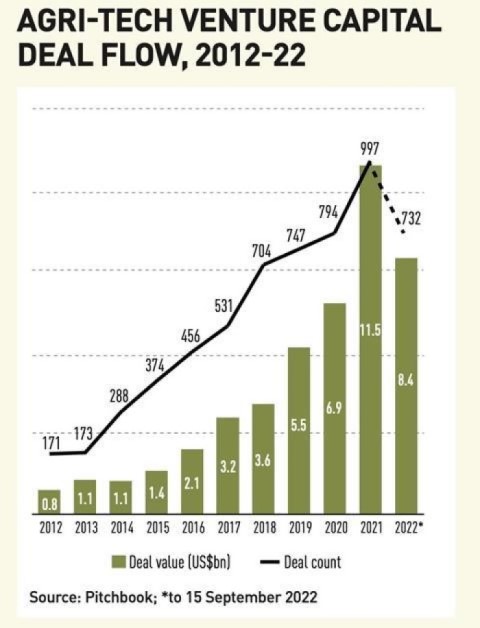

Pitchbook reports that a slight dip in investment in agriculture and food technologies in 2022 has since rebounded. The US data firm tracks global investment flows into venture capital and recorded a total of US$11.7bn going into the agriculture and food tech sector globally in 2021.

Based on inflows up to the third quarter of 2022, Alex Frederick, Pitchbook’s senior analyst, expects total investment to annualise to December 2022 at a slightly higher figure than 2021.

According to AgFunder, a VC and research firm, investors pumped US$51.7bn in venture capital into start-ups working on food and agriculture technologies in 2021 – an 85% increase over 2020.

On closer scrutiny, the AgFunder 2022 report shows US$18.9bn of investment going to upstream activities, ranging from biotech to farm management to novel farm, robotics and equipment in 2021. The rest (US$32.1bn) went into downstream deals, dominated by online logistics and e-grocery.

In total, AgFunder says, there were 1,241 downstream deals, with the biggest valued at US$3bn. Upstream deals were smaller in size and more plentiful (1,846). The largest was US$500m.

AgFunder reports that records on capital raisings are being broken in India, Asia-Pacific and Europe. India chalked up US$4.6bn for agri-tech and food-tech in the financial year ending 31 March 2022, while Asia-Pacific registered US$15.2bn. The latest numbers take investment in Asia-Pacific to more than US$55bn over 10 years, accounting for 30% of global food tech and agri-tech funding.

Some US$9.2bn was invested in agri-tech and food-tech ventures in Europe in 2021, according to AgFunder. As with other regions, investors in Europe mostly backed online grocery ventures and other asset-light downstream technologies. European e-Grocery start-ups raised US$4.2bn – 43% of Europe’s total investment capital.

Frederick says the top growth sector from Pitchbook data in 2022 was “insect farming”. Animal nutrition is the primary target market for insect farming. Capital raising by a group of companies, such as Innovafeed and Ynsect, was 126% higher in the first three quarters of 2020 than all of 2021.

Controlled environment agriculture (CEA) farm operators raised US$1.70bn year to date and CEA farm component manufacturers raised US$307.5m year to date – up 123% for the first three quarters of this year versus all of 2021. It is also worth mentioning that annual deal values for land were higher for the first three quarters than for the same period of 2021, and will be a record high in 2022, says Frederick.

But investment in technologies for the agriculture sector remains woefully low. Krishnan says: “Energy transition [funds] last year raised US$750bn. By comparison, food transition attracted investment of just US$30bn to US$40bn.”

Boer says the largest fund might have raised US$500m, with many smaller funds raising upwards of US$50m; the most common size ranges from US$150m to $300m.

Anders says agri-tech is a young industry at the relatively early stages of attracting institutional investment. “It is only in the last three years that fund maturity and company investment rounds have become large enough to attract later-stage investors and pension funds.”

He recalls that when Anterra kicked off its first fund in 2013, the entity raised US$50m, and the total size of global agri-tech investment was around US$350m.

Anterra Capital, which says it invests in “visionaries who are building the food systems of tomorrow”, comes out of Rabobank, a leading global agriculture and food bank. Its first fund was backed by Rabobank and the balance sheet investment arm of Fidelity.

“It is only in the last three years that fund maturity and company investment rounds have become large enough to attract later-stage investors and pension funds”

Adam Anders

Encouragingly, a twinkle of interest in agri-tech and food-tech among institutional investors is now evident elsewhere. Sources say they are seeing the likes of Caisse de dépôt et placement du Québec (CDPQ) and a small number of pension funds enter the market. CPDQ has set up a C$500m climate fund which, among other things, will invest in food and agri-tech. It is building a team and expertise that will take it beyond farmland. Others like Nuveen, backed by pension funds, are starting to look into emerging growth categories.

Boer says his firm is looking at a second close of his inaugural fund in 2023 to raise a further €100m, and he expects to see first-time pension capital. In this close, institutional investors will be insurance companies and funds of funds, he says.

Anterra Capital closed its most recent fund in early 2022, raising $260m from institutional and private investors, including Rabobank, Fidelity, Temasek, Novo Holdings, a Danish investment company Tattarang, the private investment vehicle of Andrew Forrest, one of Australia’s richest men, and the Environmental Agency Pension Fund of the UK.

“We invest across the value chain in biotech – covering genetics to biological – and digital technologies,” Anders says. “On the digital side, investment ranges from bio-informatics to on-farm advice and direct-to-consumer food propositions.”

Krishnan says: “The future of the global food system will require decarbonisation, decentralisation and deglobalisation, and is heading to where consumers want their food system – more nutrition, more flavour and affordability.

“The Millennials and Generation Zs now make up 40% of the world population, and they have different expectations of food. People look at all the problems facing the global food system with a lot of anxiety, but I look at it as opportunity. I think both the role of real assets and technology in partnership will be critical. As an example, we are seeing increasing interest in regenerative agriculture, particularly in regenerative organic agriculture.”

Going down this route, Krishnan says, will create higher returns for farmland investors because there will be higher farm commodity prices along with cost savings from not using today’s high-cost fertilisers.

“We believe this is a long-term trend. We are comfortable that the agri-tech sector has a lot of tailwinds that will get it through these volatile times”

Malcolm Nutt

This means a change in mindset from extractive to regenerative mining of the soils. “When organic matter in the soil is increased, it can hold more water and be more resilient,” he says.

“I think we have to pivot to carbon-neutral or carbon-negative farming. Polyculture crops will gradually become the norm. Instead of two, there may need to be five rotations of crops, introducing niche, higher-value commodities into the rotation.” Higher rotation is beneficial, he says, because it creates greater biodiversity.

Krishnan also points to demographic changes, as younger people move into farming. The new generation of farmers are more tech savvy, “willing to be more risk-on about it”, he says. “But I see this transition taking a while.”

Within the sector ecosystem, agri-tech and livestock tech are still seen as the poor cousins of food-tech. According to Anders, plant biotech is generally under-invested. He points to the fact that there has not been a new development in herbicides for more than three decades, and that investment in technology to improve animal health is still under-funded.

Agriculture and farming is a $2trn industry that is in need of innovation,” Anders says. “It is not just about substituting meat. We believe that improvement in animal health is a fundamental way to improve human health as well.”

US academic Aidan Connolly, founder and president of AgriTech Capital, says more capital is being channelled to start-ups working on food tech as they look for solutions in food waste, supply chain and food freshness.

Of US$9bn raised up to the September quarter of 2022, for example, Connolly says perhaps US$2bn went to crop tech and US$1bn to livestock tech.

“Crop tech is typically two years ahead of livestock tech today, so the livestock sector has been slowest in adoption,” Connolly says. “Crop tech is maybe 10 years behind food tech. The difference can be traced to the amount of money invested in food tech versus crop tech.”

Public reluctance to pay higher prices for food is the real deterrent to the adoption of new technologies. “You are now expected to invest in technologies that may reduce the carbon footprint for farming, but nobody is going to pay you for it,” he says. “The grocery stores are not going to pay you, supermarket food chains won’t pay you, consumers do not want to pay more – they continually complain how expensive food is.”

For generations, research and innovation in food and agriculture sectors has centred around the laboratories of global food and agri-business conglomerates. Universities and government-sponsored research institutes have been chipping away, looking for the best technologies. But, says Connolly, the level of innovation coming from these organisations has been modest. What innovation there is today is coming from start-ups which have tended to be self-funded.

Anders observes: “There are many reasons why adoption of technologies is slow. One is annual production cycles. Another is that we have very powerful corporates dominating this market, and people are emotional about food.”

Please visit the Real Assets website to read the original article– a subscription is required to view the article.